PART I: THE BROTHERS KENT

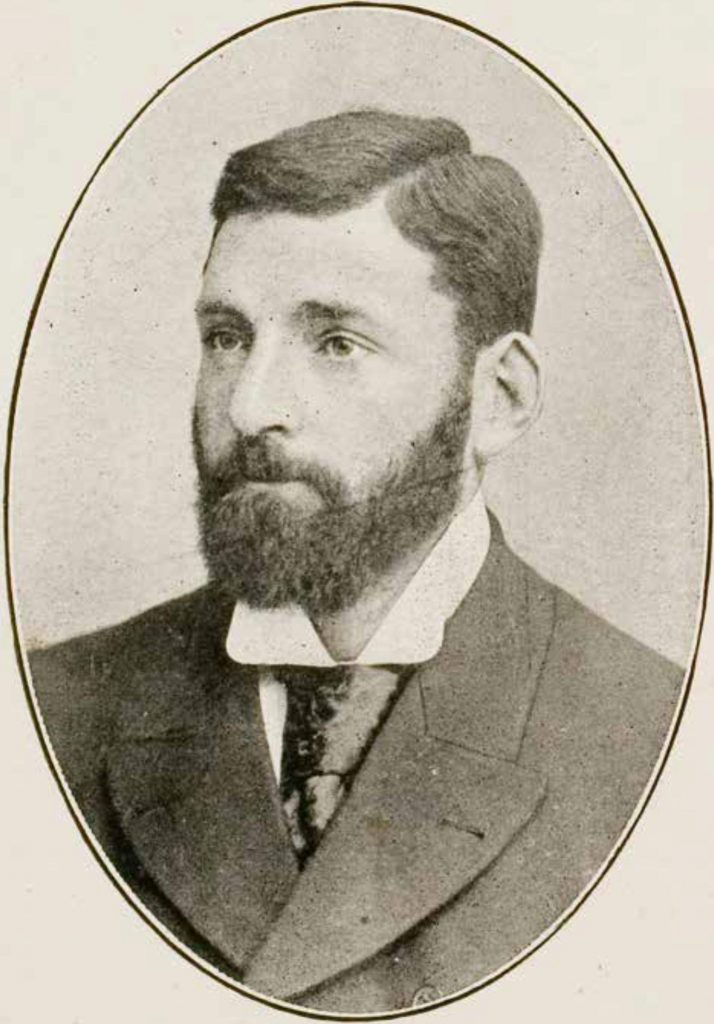

Lives tend to intertwine in small villages and had you been in Castlelyons on 23 March 1920 for the funeral of an tAthair Peadar Ó Laoghaire, then you would have seen two men—a “David Kent M.P.” and his brother William—in the crowd. An air of legend already clung to the pair, namely for a showdown with British Crown Forces during the 1916 Rising that had played out a little like the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Now middle-aged, William and David were two of the band of four immortalised by the lines: “God grant to Erin in her day of danger / Guards unwavering as the brothers Kent.”

Get close enough to David and you would see that he was missing two fingers on his right hand. He also had a habit of “limping over sideways” due to a wound received in the same encounter: stooping to lace his boots during the Siege of Bawnard, he was hit by a ricocheting bullet which left him with “a gaping wound in his side.”

Given that an tAthair Peadar had been his parish priest for near thirty years, no-one would have been surprised to see David at the funeral. Yet he may have had more personal reasons for attending. After all, in the desolate aftermath of the Siege of Bawnard, when a call came from the Kent home to “send for the priest, there is a man dying”, it must have been David who was meant for Richard hadn’t been shot yet. In any case, it was an tAthair Peadar who answered that call and who knows but the memory of him may have stuck with David a long while: especially the image of the small white-haired priest stooping over him to administer last rites (and perhaps a few words to comfort the dying) as he lay there stricken.

Standing in Castlelyons churchyard that day in 1920, had David’s thoughts turned to the other two who had fought alongside him at Bawnard, then he wouldn’t have had to look far for one. He—youngest brother Richard—lay just across the way in the Kent family burial vault. But if David had looked there for the fourth, then he would had looked in vain as Thomas was buried some twenty miles away. CONSTABLE SHOT DEAD DURING A SEARCH a newspaper headline blared the day after the shootout at Bawnard and it was for this crime (as well as “aiding and abetting an armed rebellion”) that Thomas was executed in Cork Detention Barracks (later Cork Prison) on 9 May 1916.

To add to his family’s loss his burial in a prison meant that visits to his graveside were strictly curtailed. Rationed to once a year in fact when a few people were allowed in to say a few prayers by his grave. Or at least the rough spot where they thought he was buried as they couldn’t be 100% sure that they were standing in the right place. Not when, as attested by one inmate of Cork Detention Barracks, for a long time after his death there was nothing to show “where Thomas Kent was executed and buried … except for a faint crude cross” chalked on the prison-yard wall nearby. A wooden cross and then a marble plaque were erected with time but by then memories had grown so hazy that not even prison authorities could say for sure where he was buried. His exact whereabouts remained unknown until 2015 when remains were discovered during renovations of Cork Prison and these were identified by DNA testing as Thomas’s. Near one hundred years after his hasty burial in unconsecrated ground, Thomas Kent was finally offered a proper funeral by Taoiseach Enda Kenny. The Castlelyons man’s descendants accepted on his behalf.

A date was set for the State Funeral—Friday, 18 September 2015—and anyone in Castlelyons that day would have known that something historic was afoot. To know that you need only have seen the massive crowds in the village that day and the who’s who of the Irish political world filing past the cameras into St Nicholas’s church to pay their respects. Yes, hearing Taoiseach Enda Kenny speak about how, in pursuing “the goal of Irish freedom”, Thomas Kent had “paid the ultimate sacrifice”, it was hard not to feel that the 1916 rebel’s return home had finally put Castlelyons on the map.

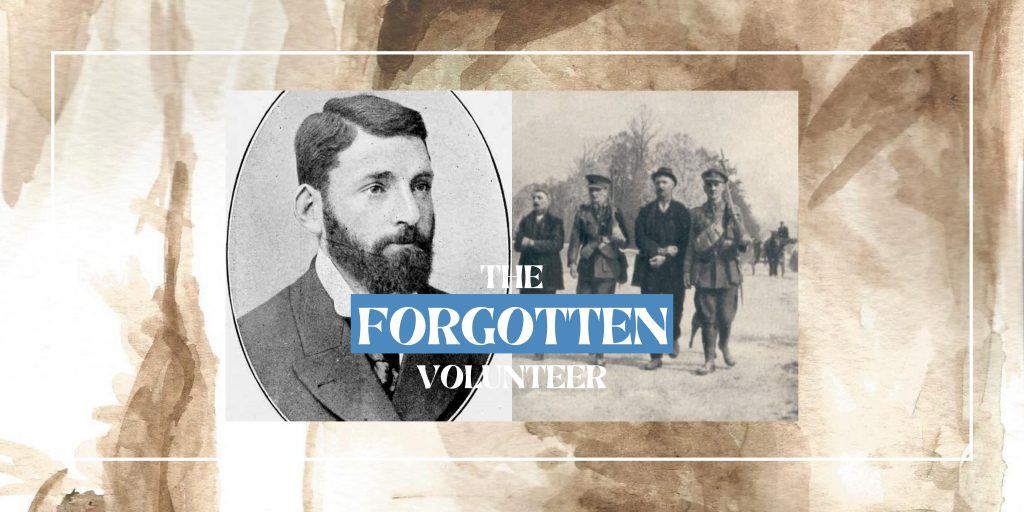

But, in terms of summing up Thomas’s dramatic change in fortunes, it was Cmdt. Gerry White who said it best when, delivering the eulogy at the funeral, he said:

For ninety-nine years Thomas Kent’s remains lay behind the walls of a prison … It was a lonely grave in a lonely place. For many people he remained an obscure figure, the “Forgotten Volunteer”, someone they knew Kent Station in Cork was named after, but little else. Today, however, all that is changed. Today, because of the recent discovery of his remains, Thomas Kent has once again become someone who is very much in the present. Today, members of Óglaigh na hEireann, the Irish Defence Forces, will render the military honours that were denied him 99 years ago. Today, he will no longer be the Forgotten Volunteer. Today, after 99 years, Thomas Kent is finally coming home.

Speaking of making someone seem “very much in the present,” three items offered up at Thomas Kent’s funeral gave a vivid sense of the man in life. The first memento—a set of rosary beads—brought one uncomfortably close to his final moments as he died clutching a set of rosary beads, drawing strength from them no doubt as—having refused a blindfold—he stared down the barrels of the 12-man firing squad charged with executing him.

Given how committed he was to his Temperance oath, the second memento, a Pioneer pin, also vividly evoked him. Thus it was likely his doing that saw the Castlelyons company of Volunteers become the first teetotal branch in the country. The Pioneer Pin also tied in closely with his final days as he was wearing his temperance badge when arrested. A sign of what it meant to him, he made sure to entrust it to the man who kept him company on his last night on earth—prison chaplain Fr Sexton—charging him to return it “untarnished” to the one who had bestowed it on him in the first place: Fr Aherne of Castlelyons. His commitment to abstain from alcohol didn’t end there, however, as offered a drink to steady his nerves before execution, he is meant to have said: “I have been a total abstainer all my life and a total abstainer I’ll die.”

It was with the third memento—a copy of an tAthair Peadar’s autobiography Mo Scéal Féin—where the close association came a little unstuck, however. Not that Thomas’s commitment to reviving Irish was in doubt, far from it (see below). Just that seeing one of an tAthair Peadar’s books offered up in memory of him might have given the cozy impression of them as the best of friends. When the reality was likely more complicated: an tAthair Peadar growing increasingly wary of his parishioner Thomas the more he became involved with the Irish Volunteers. But more on that later. For now let us delve into the background of the man who went down in history as the only rebel (aside from Roger Casement) to be executed for the 1916 Rising outside Dublin.

Born on 29 August 1865, Thomas was the fourth of nine children, raised at Bawnard, a farm of 200 acres in Coole Lower, Castlelyons. He was only eleven when his father died, leaving his mother Mary to raise seven sons and two daughters alone. No easy task but Mrs Kent was a formidable woman and her ceaseless efforts on their behalf left a deep impression on her children, even when men and women grown. In sign of this perhaps her son liked to go by “Thomas Rice Kent”, using his mother’s maiden name as his middle name.

Though he had hardly more than a primary-school education, he had literary leanings from a young age, described as “always scribbling something”. Indeed, his love of writing proved lifelong, so much so that, when booked in at the sergeant’s desk following the Siege of Bawnard, the only things in his pockets were a few coins and some poems he had written while on the run the previous week.

PART II: BOSTON BOUND

Reminiscing about Thomas in his prime, relatives described him as tall and good-looking with “many admirers on the dance floor”. Such qualities would undoubtedly have recommended him when he emigrated to Boston in 1884, age nineteen. He joined the Philo-Celtic Society and setting up an Irish society under its auspices would prove his entrée to Boston-Irish society. He climbed the ranks and it wasn’t long before he was serving on the Philo-Celtic Society’s Board of Directors.

He must have been well-liked in Boston as evident from the almost pining note in reports of his absence on trips home, like this one published in the Irish Echo in July 1887: “We have not heard yet from Brother Kent . . . It is, however, a consolation to know that wherever he travels he will work in the interest of the Irish language movement.”

Patrick Pearse once said that Tír gan teanga tír gan anam [“A country without a language is a country without a soul”] and this was certainly Thomas’s credo as clear from a letter of his published in the Gaelic Society Irish American Weekly in January 1889:

It is a shame for Irishmen not to know their own language. It is a sin for them not to help in its revival, it costs but very little to belong to an Irish Society … Wake up, brother Celts, and join in the good work of preserving your language … and save the old tongue from total extinction.

Trusting this letter may help some of them to see the light, and that my fellow-countrymen will not be indifferent to their language in future.

I remain, gentleman,

Respectfully yours,

Thomas Rice Kent.

By the time Thomas wrote this amiable call to arms, he was already five years in Boston and one gets the sense that he had no intention of returning anytime soon. Especially not since setting up his own publishing company—“Thomas Rice Kent and Co.”—in May 1889. Yet, just a few months later, by September 1889, he had returned home for good. Drawn back by his brothers’ trial for “The Coolagown Conspiracy” (see Fr Ferris page). This would prove a turning point, sending him off down a very different path.

PART III: HOMECOMING

The next two years would pass in a blur of protests and imprisonments, all in the cause of evicted tenant farmers, but the Kent brothers became so disillusioned by the Parnell split in 1890 that they withdrew from politics altogether for a while. Perhaps as a way to fill the void, Thomas found himself reverting to the pursuits of happier days in Boston and it wasn’t long before he was participating in concerts and plays in Castlelyons as well as reciting his poems publicly on occasion. Organiser of “Celtic Music Festivals” while in Boston, he kept up that interest in Castlelyons, local man Paddy Newton remembering meeting Thomas “at the platform in Abbey Lane, near his own house. He had a lively interest in traditional native music and dancing, and often sat near me listening to my playing when I used to play for the dancers.”

He found even more of an outlet when there were calls to set up a branch of the Gaelic League in Castlelyons in 1912 and, indeed, in a poem from this time, Thomas is seen leading a delegation to seek the parish priest’s blessing for the foundation of the same:

Tom Kent was there amongst them

And very plain was he

He proposed that all should

Go and see the great PP

He said unto his Reverence

We have one word to say

We want to learn this Irish

And keep it from decay

So now within your parlour

You will make for us a rule

That in order to get some shelter

We’ll have to get the schools.

He said that he would give the school

to learn this language grand

and the committee they were thankful

For they shook him by the hand.

Not only did “the great PP” give the go-ahead for use of the school, but he also agreed to become patron of the branch so that the Castlelyons branch of the Gaelic League was formed under the presidency of an tAthair Peadar Ó Laoghaire. Over the next few years this branch “fulfilled a very useful social and recreational function … in the parish”, according to one local. Thomas was a very active member, teaching Irish, music and dancing lessons as part of the branch.

1914 was another pivotal year for the Kents as it saw them enroll in the Irish Volunteers, forming the Castlelyons company of Volunteers. Indeed, Thomas was so central to recruitment and organising companies in County Cork that many Volunteers fired their first practice shots in the woods around Bawnard with a miniature rifle owned by the Kents.

Events hurtled along from here until the date set for rebellion—Easter Sunday, 24 April 1916—and Volunteers up and down the country drilled and quietly amassed arms to be ready for it. The trouble was that the founder of the Irish Volunteers, Eoin MacNeill, had been kept in the dark about the Rising and, finding out about it at the last minute, threw everything into confusion by ordering the Irish Volunteers not to rise at Easter. Only for the Rising to go ahead in Dublin anyway, a development which caught the Kents off guard as, having complied with the order to stand down, the first they knew about the Rising in Dublin, William said, was by reading about it in the newspapers.

With renewed hope “of being called on to join other Volunteers in a fight”, William and his brothers went on the run. A tense week followed in which they hid on neighbouring farms until news reached them that “the Rising was over in Dublin” and so they decided to return home. Little did they know that this would put them on a collision course with British Crown Forces and that, by the time dawn broke over Bawnard, of the Kent brothers four, one would be dead, another badly wounded, and another a dead man walking.

Part IV: THE SIEGE OF BAWNARD

As William recounted in the witness statement he gave the Bureau of Military History in 1947, the first he knew of trouble afoot was “a loud knocking on the hall door”. Jumping out of bed, he ran into Thomas’s room to shake him awake with the words “The whole place is surrounded. We are caught like rats in a trap!” Dragging on some clothes, Thomas shouted down to those below: “What do you want?” A stern voice answered immediately: “We are police and have orders to arrest the whole family.” The Kents replied defiantly as one: “We are soldiers of the Irish Republic, and there is no surrender!”

That was not quite how the R.I.C. remembered it. From their point of view—as given by Constable Frank King in his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History in 1951—the night’s events began when “we left the barracks around 2.30 a.m. on 2nd May 1916” with orders “to arrest all prominent ‘Sinn Féiners’ in the district.” On arriving at the Kent home, the raiding party was told by their leader Head Constable William Rowe to take up position around the house so as to “cover all exits and allow no-one to escape.”

Accounts differ as to who fired the first shot: according to Constable King, Head Constable Roe had hardly knocked on the kitchen door and stated his business when there came:

a very loud and defiant answer. I believe the words were “We will not surrender until we leave some of you dead.” This answer was followed immediately by a shot.

Whereas, to hear William tell it: “The police fired a volley to which we replied and a fierce conflict began.” Regardless of who fired the first shot, there is no doubting that the R.I.C. subsequently opened up with a barrage that left Bawnard House “a wreck, not a pane of glass left unbroken.” The scale of the destruction is clear from thirty-two bullet holes left in the pantry door and a bag of flour riddled with lead.

In her eighties at the Siege of Bawnard, one would have expected Mrs Kent to take no part in the fighting but not for nothing was she eulogized as that “Spartan Irish mother” on her death in January 1917. During the Bawnard shootout, William remembered her “loading weapons” and shouting encouragement. When his shotgun jammed she even had the presence of mind to free it by pushing a stair rod into the barrel to release the trapped cartridge.

Alas, despite the Kents’ resourcefulness and pluck, the fight went steadily against them until, at 4:30 a.m., events took a disastrous turn when, in Constable King’s words: “I could see the Head Constable crouching behind a low wall on the far side of the house. Several shots rang out and I saw him fall back on the ground.” Shot in the head, the Head Constable died instantly.

Disastrous indeed as the killing of the Head Constable also signed Thomas’s death warrant as he would be blamed for it at trial. And as devastating as the night’s events were for the Kents, they were a tragedy for the other side too: Head Constable William Roe left behind five children, all under the age of sixteen, and he was evidently well-liked: “a large concourse of townspeople” accompanying his coffin to burial in Castle Hyde Churchyard.

The conflict ground on but morale-wise, the final straw must have been the arrival of military reinforcements at 6:15 a.m. From their vantage point upstairs in their Bawnard home, the Kents would have seen five trucks pull up and upwards of 50 soldiers pouring out of them, all armed with machine guns and rifles. If that wasn’t enough to get across that they had come, in Constable King’s view, “prepared for a big battle”, they made their intent chillingly clear by setting up a machine gun and pointing it at the house. The message was clear: the last three hours of bombardment may have been hellish, but things were about to get much worse. William signalled surrender soon after that by tying a piece of white cloth to the barrel of his gun and waving it out the window.

PART V: SIEGE AFTERMATH

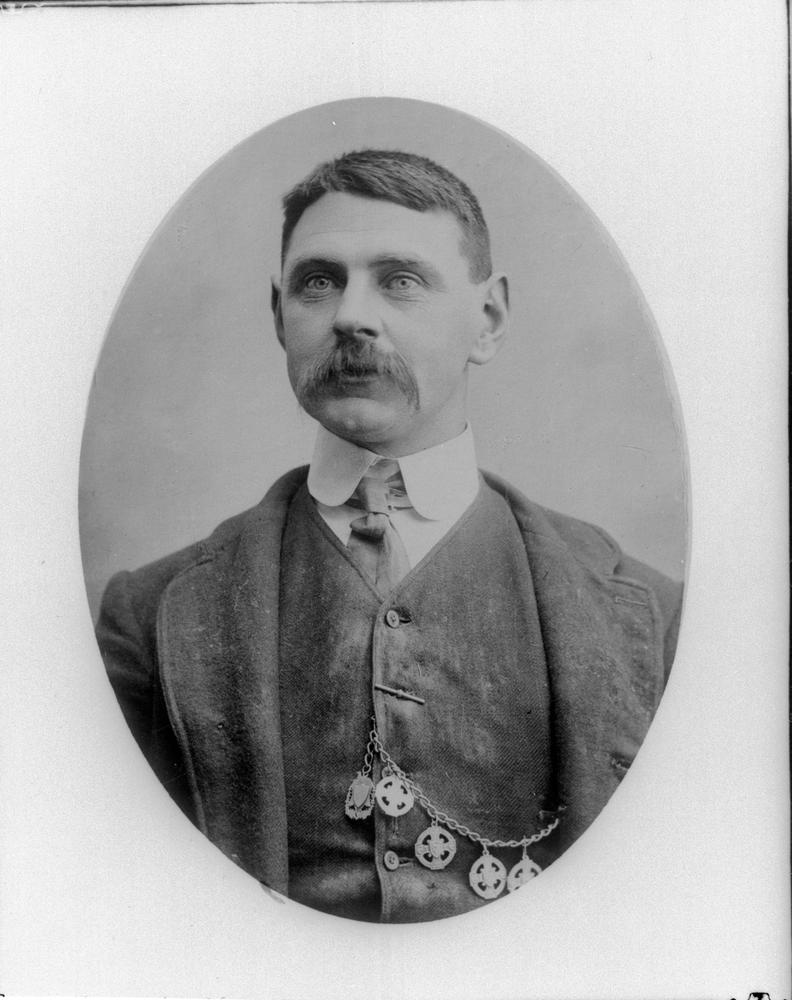

Emerging from their ruined home with their hands up, Thomas and William were immediately handcuffed. But Richard was not and “in the confusion,” tried “to escape by bounding over a hedge”. William’s wording here seems significant as it recalls the thing that Richard was most known for. As Paddy Newton recalled:

Richard Kent I first saw when he competed at the athletic sports of Conna. It was the high jump. He won it that day because even though he was at the start of his career, he jumped remarkably high – so high that it was said that he would soon be an athlete of top calibre. The prediction was proved correct: he was before long known as an expert athlete throughout the country. Often afterwards when Richard was training for the hurdle race, I and my friend William Buckley … used to help him (with a handicap part of the course).

Champion hurdler that he was, was it a case of an old instinct kicking in at a time of extreme stress? Who knows what was going through Richard’s head as he tried to make a break for it “by bounding a hedge” but he didn’t get very far before he was mown down in a blaze of rifle fire. Shot in the back, he fell mortally wounded and would pass away in Fermoy Hospital two days later.

One thing we can be sure of is that Richard’s sporting success meant a lot to him as clear from the photo below in which he has his athletics’ medals pinned proudly to his chest. Which makes it sad to learn that, according to Constable King, said medals “were stolen by the military who searched the house on the day of the arrest”.

Thomas and William narrowly escaped being shot themselves when, upon surrender:

We were lined up against a wall of the house by the R.I.C. who prepared to shoot us, when a military officer interposed himself between us and the firing party. Ordering the police to desist, he said “I am in command here. Enough lives have been lost, and I take these men prisoners of war”.

Growing increasingly uncomfortable at the actions of his colleagues, Constable King decided to belatedly act on the Kents’ request for a priest. This is where an tAthair Peadar enters the story as, in King’s words:

When Dick Kent was shot while trying to escape, I left my position without permission and went down to one of the trucks on the road and told the driver to take me into Castle Lyons for the priest. Canon Peter O’Leary was waiting at the Presbytery for a car to take him to 7 o’clock Mass. He came away with me immediately in the truck instead. When we got to the Kent house the military were still searching the house and old Mrs. Kent who was 86 years of age had been put under arrest.

The petty acts had continued in Constable King’s absence. For instance, a neighbour wanted to give Mrs Kent a cup of tea, but a military officer would not allow this as she was under arrest. More disturbingly, the Kents’ dog was shot and “one of the military chopped off a leg and hung it at the back-top of his gaiter.”

Constable King then put Mrs Kent in a truck and, allowing an tAthair Peadar to accompany her, drove them into Fermoy. Thomas and William were forced to make the same journey on foot, an ordeal for Thomas when, as William recalled, he “was not permitted time to put on his boots.” Which meant walking the five miles into Fermoy barefoot. Forced to walk behind the cart on which Richard and David lay wounded, he and William must have made for a sorry sight as they limped along in handcuffs.

PART VI: ARREST AND EXECUTION

God only knows what people thought once the bedraggled brothers arrived in Fermoy: a photograph of them taken on Fermoy Bridge (which has since become iconic) captures the moment vividly.

Looking at this photo, it is easy to imagine what questions must have run through onlookers’ minds that day when, on what they thought was an ordinary Tuesday morning, they were suddenly confronted with this strange sight. Questions like Who were these dishevelled men? What had they done that was so terrible that it required marching them through the town like a pair of common criminals? And, good God, why wasn’t that man wearing any shoes?

People were likely a little better informed when the same men (Thomas still boot-less) were marched back across the bridge the following day (3 May) and on to Fermoy Railway Station for transport to Cork City. Alighting at Glanmire Road Station (since renamed Kent Railway Station in memory of this incident), they were forced to walk once more, this time the two miles or so to Cork Detention Barracks. Which meant that Thomas’s bare feet were well and truly blistered by the time he was escorted to his cell, to await trial in solitary confinement.

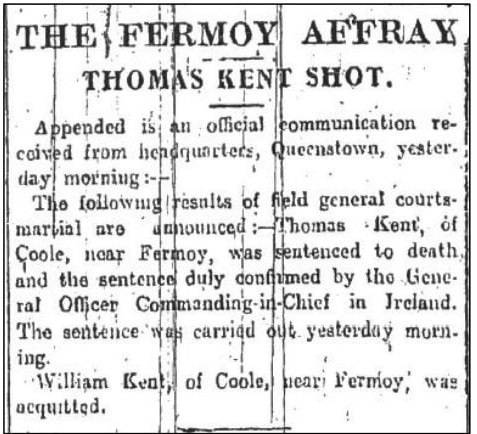

Which happened the very next day when, on 4 May 1916, Thomas and William were put on trial, charged with the “wilful murder” of Head Constable Rowe. Though it couldn’t be proven that it was he who fired the shot that killed Head Constable Roe, Thomas was found guilty of his murder and sentenced to death by firing squad.

William was acquitted, thanks in part to people like Constable Frank King who testified at trial that he “was a quiet, inoffensive type who had no ‘Sinn Féin’ activities.” This was not the only time that a Kent brother was saved by the intervention of someone on the other side. For instance, as William recalled:

But for the kindness of Dr. Brody, David would have been immediately courtmartialled and probably shot. Dr. Brody kept him under medical treatment in the hospital and refused to certify him fit for removal until things had calmed down somewhat.

Compare this to the fate of 1916 leader James Connolly who was certified fit for execution despite being so badly injured that he couldn’t stand to face the firing squad and so had to be shot sitting down. Lucky for David that someone on the British side was willing to stick his neck out for him as, thanks to Dr Brody’s stalling, tempers had cooled enough by the time he stood trial (two weeks later) that his death sentence was commuted to five year’s penal servitude.

There was to be no reprieve for Thomas, however, and, at 6 a.m. on 9 May 1916, he was taken out into the exercise yard of the Cork Detention Barracks and shot by a twelve-man firing squad. He showed courage in his final moments, dying, in the words of the British officer in charge, “very bravely, not a feather out of him”.

PART VII: DAMNATIO MEMORIAE

A sad end for Thomas but more distressing yet was how he was treated after execution: tossed into a shallow, unmarked grave, no coffin, just doused in quicklime to speed decomposition. And lest we think this some passing cruelty, it was not. Rather it was deliberate policy, coming straight from the top as it was Major General Sir John Maxwell himself—the man charged with quelling the 1916 rebellion in Ireland—who gave the order for this degrading treatment on the grounds that:

Irish sentimentality will turn those graves into martyrs’ shrines to which annual processions etc will be made. [Hence] the executed rebels are to be buried in quicklime, without coffins.

No doubt what had spooked him in this regard was the funeral of Cork Fenian Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa the previous year. As his grave had indeed become something of a shrine for republicans following Patrick Pearse’s impassioned graveside address at his funeral. Thomas made the trip to Dublin to attend the Fenian’s burial in Glasnevin cemetery on 1 August 1915 and so he would have heard Pearse utter the famous lines:

They think that they have pacified Ireland. They think that they have purchased half of us and intimidated the other half. They think that they have foreseen everything, think that they have provided against everything; but the fools, the fools, the fools!– they have left us our Fenian dead; and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.

Well, General Maxwell was determined that Ireland would not hold Pearse’s grave at least which is why he ordered a mass grave dug in the exercise yard of Arbour Hill Prison. Into this Pearse was thrown along with the 13 other rebels executed. In death these condemned men were to be allowed none of the common decencies one would expect at a funeral: no coffin, no headstone, not even a priest to say a few prayers as they were tipped into a mass grave and had quicklime poured over them. The idea in denying them the ordinary trappings of burial was to make them non-entities in the eyes of the world at large. Doubly so given their burial in a prison yard as that was designed to make their graves difficult of access. The hope was that, without a grave to visit, it would be a case of out of sight, out of mind for the general public. General Maxwell wanted to avoid a repeat of the funeral of O’Donovan Rossa at all costs. To ensure that his plan to condemn these men to obscurity worked, he denied multiple requests from the families of the executed men to have their remains returned to them.

The Romans called this damnatio memoriae and for them it meant obliterating all traces of a traitor from the public record: be that by smashing statues, defacing pictures, or chiselling out all mention of the traitor from inscriptions. For Thomas, convicted of “assisting the enemy” and “waging war against his Majesty the King”, it meant the same dehumanising treatment as the executed rebels in Dublin, complete with burial in a prison yard to ensure that people could seldom visit his grave. All this to make him an abject example to intriguers everywhere.

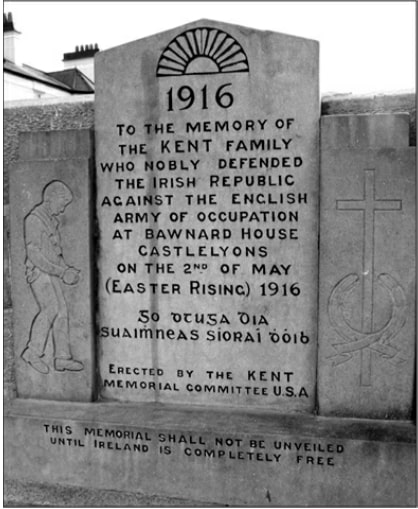

The trouble with removing all traces of a person to make it seem like he never existed was that the more authorities tried to ensure that Thomas Kent became “The Forgotten Volunteer”, the more determined that made people to keep his memory alive. So, for example, a Thomas Kent Camogie club sprung up within a year of his death; soon followed by a Fermoy Sinn Féin club named in his honour in 1918. And then, of course, there was the Thomas Kent Pipe Band which is still going strong. As long as groups like this existed, even with his grave shut away behind prison walls, his memory could never die.

Which makes it fitting that the memorial outside Castlelyons church commemorating “Thomas Kent executed 9th May 1916” should end with the quote: “IRELAND UNFREE SHALL NEVER BE AT PEACE” – P. H. PEARSE.

I think what Pearse meant was that the foreign occupier’s mistake was often to assume that killing off the rebels meant killing off the threat. But if you took the long view of history, as Pearse did, then you’d know that the rebels’ death was only the beginning. For, in his speech in Glasnevin cemetery in 1915, Pearse was contending that as long as brutal reprisal was England’s only answer to Ireland’s quest for freedom then the two countries would stay locked in an endless cycle of suppression and rebellion: the harsh crackdown after each rebellion only sowing the seeds for the next one by creating fresh resentment. In serving as reminders of past brutalities then, the graves of executed rebels were a powerful weapon in the war of attrition that was Ireland’s relationship with England and, over the long haul, so Pearse believed, it would be the British will to stay rather than the Irish will to fight on that would grind down first. Had he lived to see it he would have pointed to Thomas Kent’s grave as a case in point: in trying to consign him to oblivion, colonial authorities had only ensured that his memory would spring up ever new.

PART VIII: MIXED FEELINGS

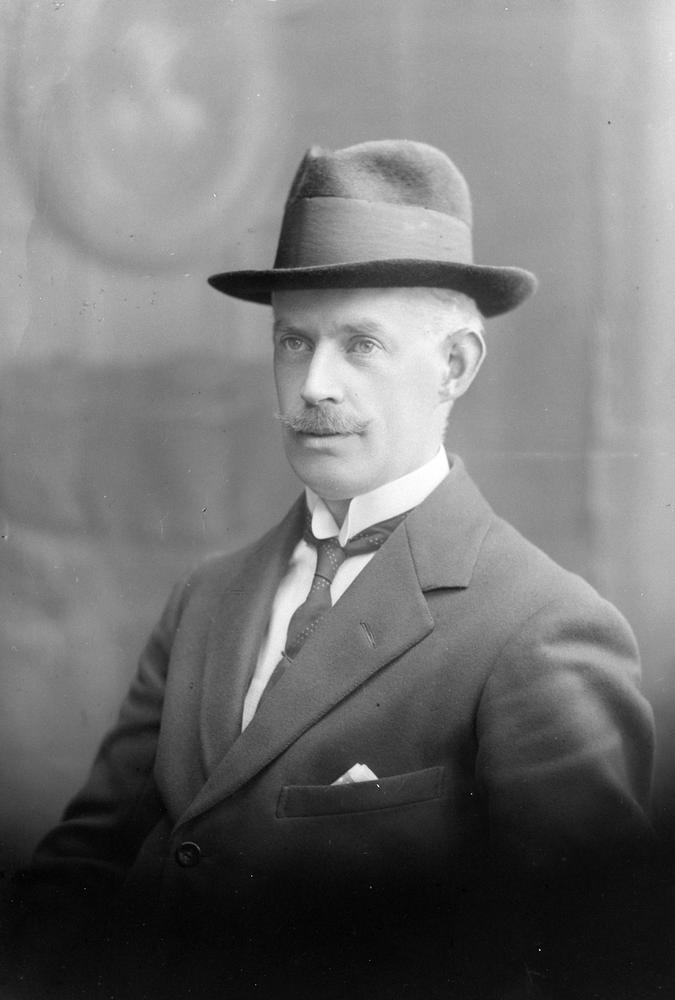

As it turned out, outrage at how badly the 1916 leaders were treated did indeed hasten the demise of English rule in Ireland. But this is to read history backwards for those left to pick up the pieces after the Rising did not have the benefit of hindsight. So, for many of them it may have seemed more senseless waste than brave push for freedom. In his mixed feelings, an tAthair Peadar embodied the ambivalent reaction of many Irish people at the time. To return to the morning of the Siege of Bawnard for a moment, in seeing him in the truck next to Mrs Kent, many people assumed that he too had been arrested. Had this rumour gotten back to him, it would likely have irked him to know that some thought him in league with the rebels. For he was dead-set against any close ties between Irish-language activists and armed rebels. As this 1903 letter of his makes clear:

Our movement is like Caesar’s wife. It has to be kept “above suspicion.” Its purpose is the preservation of the language and nothing else … ‘We are ‘nonsectarian’ and ‘nonpolitical’ … I’ll fight the devil himself sooner than let this false position continue!

And certainly by the time Thomas had risen to Commandant of the Galtee Volunteers while still an active member of the Castlelyons branch of the Gaelic League, he had come to embody what an tAthair Peadar feared most. For, in drawing the language movement into sectarian politics, he went against the ecumenical spirit in which the Gaelic League was founded. After all, it’s first president, Douglas Hyde, was a Protestant and a genial soul to boot with a knack for presenting the Gaelic League as open to all, regardless of race or religion, as long as they had a grá for “the grand old tongue”.

Compare this to Thomas then who, at least in his more war-like moments, evidently agreed with the sentiment that Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori [“It is a sweet and honourable thing to die for one’s country.”] As clear from this poem which he wrote awaiting orders to mobilise in the run-up to the 1916 Rising:

Let him who feels shame for his ancestor’s story,

Begone from our pathway – let ours be the glory.

We’ll conquer or die as our fathers of old

Have died for the land of the green, white, and gold

So, when they were woken by a knock in the dead of night, were the Kents right to resist arrest? Ask the makers of the plaque on Fermoy Bridge (erected in 1966) and the answer would likely be a resounding “Yes”. As clear from their framing of the Kents’ actions that day as “nobly defend[ing] the Irish Republic against the English army of occupation.” But is that really how the ordinary man and woman on the street would have reacted when news of the Siege of Bawnard first broke? Not to judge by the reportage in the nationalist press in the days following. The Cork Examiner, for instance, making clear their unwillingness to portray the Kents’ actions in a heroic light by dubbing their shootout with the police as “The Fermoy Affray”.

Indeed, the day after the confrontation at Bawnard (May 3), The Cork Examiner portrayed it as a senseless tragedy: “The sad affair has caused quite a sensation in the town and district … The whole sad disturbances are deeply deplored by the people of Fermoy who have always lived in the greatest good feelings with one another and with the authorities.”

To take a wider view, reporting on the Rising in Dublin, the Wicklow People dismissed it as the work of a bunch of “feather-heads and dreamers”. The Roscommon Herald was equally derisive, describing the 1916 leaders as a lot of “crazy poets”. This may strike us as craven talk now, reading it in the context of an Ireland that has been a Republic for more than seventy years. But to regard it as such is to do a disservice to the people who lived through it for the thing about being caught up in tumultuous times is that it is seldom clear who will end up on the right side of history. To bring this back to the Kents, when Richard’s coffin was carried through Fermoy, some people knelt on the pavement and wept on seeing it pass. But others booed.

Against this, if moderates like an tAthair Peadar had had their way then Ireland would likely still be part of the United Kingdom. It was only because of people like Thomas—men and women willing to throw themselves against impossible odds—that they eventually made holding onto Ireland more trouble than it was worth from the British point of view.

PART IX: SEA CHANGE

People can disagree and still pull together in a crisis and this proved to be the case with an tAthair Peadar. So, when the Kent brothers wanted someone to hear their confessions while on the run during Easter week 1916, an tAthair Peadar met up with them in secret in a neighbour’s home. He also “came away immediately” when Constable Frank King informed him of the shootout at Bawnard. What he saw that May morning at the Kents’ home likely shook him as well as opening his eyes to how far British authorities were willing to go to maintain their grip on Ireland.

Indeed, in the month after Thomas’s execution, he seems to have slowly undergone a change of heart. So much so that by 19 June 1916, he could write:

Dear Seamus,

Just like you, my feelings about the Rising in Dublin have changed. At first I was furious at the lads for being so reckless. But then when the executions happened, without any need for them, my anger switched to the other side …I’m telling you, Lloyd-George is playing a dangerous game. I hope that the men of Ireland will not make a foolish bargain.

May God direct us!

Your friend,

Peadar Ua Laoghaire.

In this he reflected the sea change in public opinion: whereas many Irish people had been on the fence about independence before the Rising, seeing how badly the rebels were treated in its aftermath galvanised many into the push for freedom that would result in the Irish Free State just six short years later.

So, that morning in Bawnard, could Thomas and his brothers have known, in the mounting their desperate last stand, that they would end up tipping the scales of history? I don’t think so but perhaps that’s what made them heroes in the end: fighting for a freedom they knew they’d never see in the hopes that others would benefit down the line.

Now that you know a little more about him, why not pay a visit to the Kent family grave where you will see Thomas’s name newly inscribed next to his brothers. Then maybe spare a thought for Castlelyons’ Rebel Poet, ninety-nine years an exile, now finally come home.

SOURCES

“Blog: Thomas Kent & Cork’s 1916 Rising.” 14 May 2016 <https://www.rte.ie/news/2016/0514/788191-thomas-kent-and-cork-1916-rising/>.

Britway – Castlelyons – Kilmagner: Reunion 1991. Cork: Castlelyons Committee, 1991.

“Kilmainham Tales 1916.” < http://www.kilmainhamtales.ie/1916–burials-at-arbour-hill.php>.

Duncan, Mark. “Reporting the Rising: Press Coverage of Easter 1916.” < https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/reporting-the-rising>.

Hoare, Brendan. “The Kents of Bawnard. 2007 <http://castlelyonsparish.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/The-Kents-of-Bawnard-by-Brendan-Hoare.pdf>.

Kent, William. “Statement by William Kent on The Fight at Bawnard House, 2nd May, 1916.” Óglaigh na hÉireann: Military Archives < https://www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/bureau-of-military-history-1913-1921/reels/bmh/BMH.WS0075.pdf>.

King, Frank. “Statement by Frank King on the Arrest of the Kent Family at Castlelyons, Co. Cork, 2nd May 1916”. Óglaigh na hÉireann: Military Archives < https://www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/bureau-of-military-history-1913-1921/reels/bmh/BMH.WS0635.pdf>.

McGreevy, Ronan. “1916 court martials and executions: Thomas Kent.” Irish Times 3 May 2016 < https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/1916-court-martials-and-executions-thomas-kent-1.2631112>.

Ní Mhaonaigh, Tracey, Ed. Tháinig do Litir: Litreacha ó Pheann an Athar Peadar Ó Laoghaire chuig Séamus Ó Dubhghaill. An Daingean: Sagart, 2017.

O’Brien, Eilish and Pat. Mise an Mac San: Remembering an tAthair Peadar Ó Laoghaire. Cork: Sciob Sceab, 2018.

Ryan, Meda. Thomas Kent: 16 Lives. Dublin: O’Brien P, 2016.

“The Executed Thomas Kent.” The 1916 Rising: Personalities and Perspectives. National Library of Ireland. 15 April 2022 <http://www.nli.ie/1916/exhibition/en/content/executed/thomaskent/>.

“Thomas Kent: The Forgotten Volunteer No Longer.” The Examiner 18 Sept. 2015. < https://www.irishexaminer.com/news/arid-30696604.html>.