Part I: The Land League Martyr

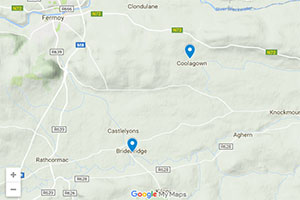

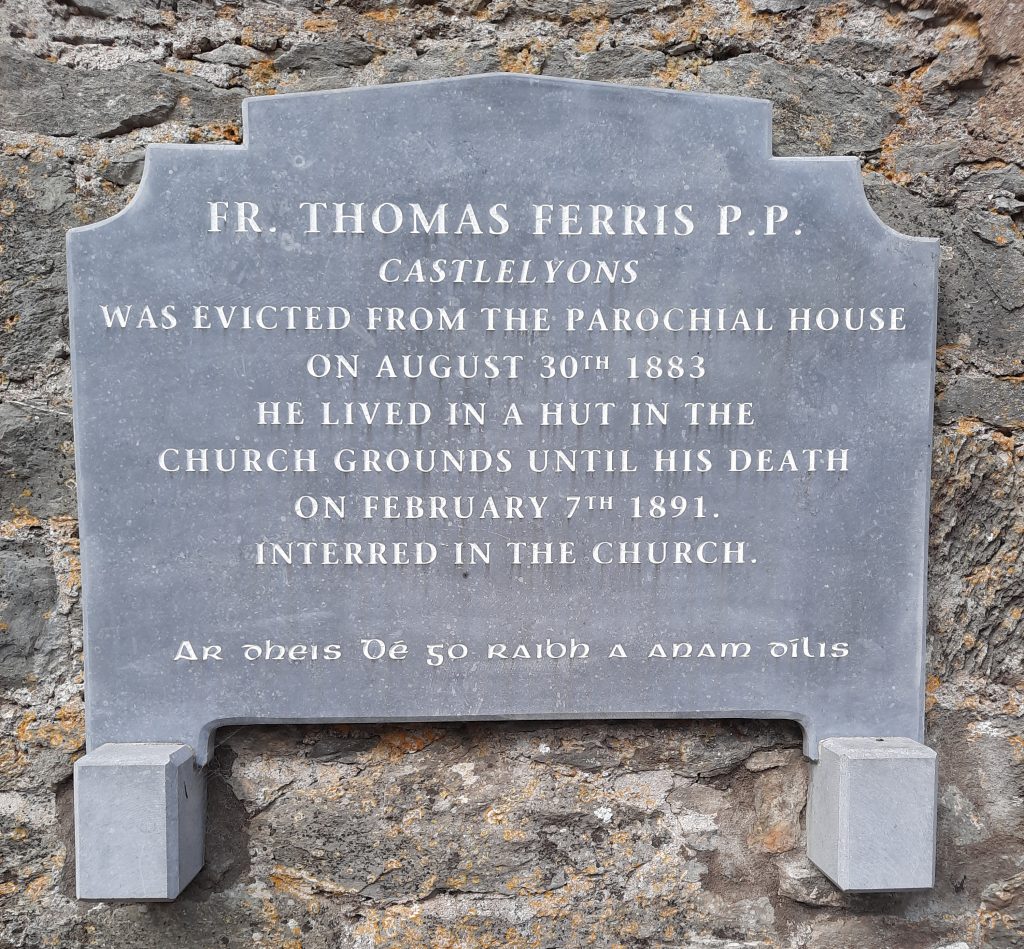

If on the trail of the “historic trio” commemorated on the info board, you will find two of them buried in Castlelyons churchyard but you’ll have to head into St Nicholas’s Church to find the third. Head up the aisle and high on the wall on the left-hand side you will see a plaque of whitish marble. Squint to read the blackened lettering and you’ll see that it was erected:

IN MEMORY OF

THE REVEREND THOMAS FERRIS

PARISH PRIEST OF CASTLELYONS AND COOLAGOWN

WHOSE MORTAL REMAINS REPOSE BENEATH.

How to sum up a life? Well, according to his marble epitaph “HE WAS A HUMBLE AND DEVOTED PRIEST” (so far so expected for a man of his era and station) but, wait, it gets more interesting towards the close, describing him as:

AN ARDENT LOVER OF HIS

COUNTRY, IN WHOSE CAUSE HE EVER LABOURED

ASSIDUOUSLY, AND SUFFERED NOT A LITTLE

DURING THE CLOSING YEARS OF HIS LIFE.

“Suffered not a little”? Shades of the martyr about that but, alas, his epitaph neglects to go into specifics as to what tribulations exactly beset his later years. Luckily, a ballad composed in Castlelyons in 1889 was more forthcoming:

We have brave Father Ferris

Who is true to Ireland’s cause

Whose Celtic blood would not submit

to Balfour and his laws.

With bayonets fixed he was forced out

And mansion left in ruins

And now he dwells in a lonely hut

Surrounded by the tombs.

O Erin dear, keep bleeding

We’re not sure of better times

For those landlords and their agents

Have charged us with great crimes.

The “mansion left in ruins” must be Castlelyons Parochial House (the balladeer presumably thinking that house’s former name, “Prospect Cottage”, genteel enough to style it a mansion) and “those landlords and their agents” a clear reference to the Land War, a grassroots campaign for tenant farmer rights waged in the 1880s. To understand the issue that consumed Fr Ferris’s later years, one must think oneself back to a time when only 3% of Irish farmers owned their own land. The rest, a whopping 97%, rented their land and were, moreover, “tenants at will” which meant that their landlord could evict them anytime he liked, usually to install new tenants at a higher rate.

Eventually, tenant farmers up and down the country had had enough and they banded together to demand the “three F’s”: that is, fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure.

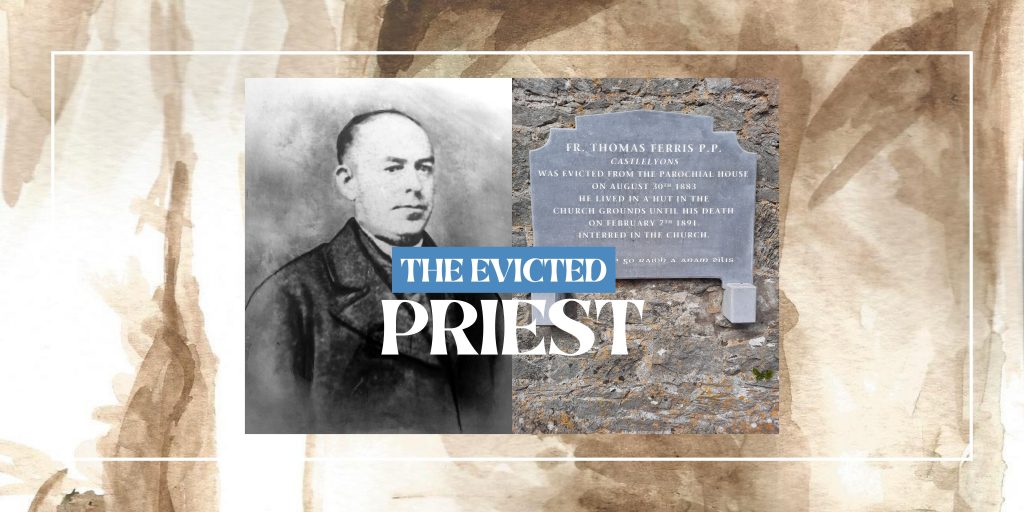

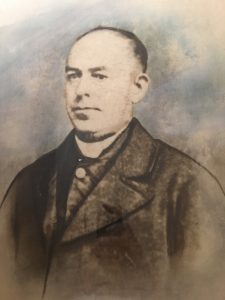

As for what kind of man Fr Ferris was, well, there is this photo of him for starters. To look at him, you’d think him a mild-mannered sort, a little bemused perhaps at having his photo taken. Yet, as we shall see later, that mild look hid a steely resolve that landlords pitted themselves against at their peril.

As for his origins, he was born in the Magnier’s hill area of Youghal in 1832. Given that Magnier’s Hill is part of Youghal town today, it’s hard to know whether that meant he grew up more in the town than in the countryside, but he certainly came to feel a fierce solidarity with his rural parishioners, particularly following his appointment as P.P. of Castlelyons on 8th September 1879. A prophetic start date (given the direction that the rest of his life would take) as this coincided, almost exactly, with the foundation of the Land League in October 1879.

Indeed, he wasn’t long in the parish when the first meeting of the Castlelyons branch of the Land League was held on 5th June 1880, at which he found himself thrust to the fore when, as reported in the newspaper, “the Rev. T. Ferris, P.P., was moved to the chair amidst great applause”. He seemed pleased with his election, describing the meeting as “a grand success”. Things bubbled away like this for a while, local woman Mrs Mary Smith remembering that “when the agitation was at its height there used to be meetings every Sunday after Mass about not paying the rent.”

Until these restive rumblings came to a head in the summer of 1883 when, following Land League rules, Fr Ferris withheld his rent from his landlord John Walter Perrot. In its place, he offered what the rent rate for Prospect Cottage had been when first leased as the parochial house some thirty years before. This reduced rent was refused and a writ of eviction duly issued, the date set for 23rd August 1883, only for the eviction to be called off at the last minute. For what reason is hard to say but perhaps, in the standoff over rent, John Walter Perrot hoped that Fr Ferris would blink first. After all, that’s how these things usually went: the threat of eviction was often enough to quieten the tenant.

The only problem was that Fr Ferris showed no signs of backing down and so the eviction went ahead eight days later on Thursday 30th August 1883. Again, one wonders at the timing: were the evictors hoping to keep a low profile by carrying out the eviction mid-week? If so then they badly miscalculated as Fr Ferris and his supporters were determined to make a scene. The first part of their plan triggering as soon as the evicting party were spotted in the locality: the chapel bell began to toll incessantly as a signal to the people that the eviction was taking place. The evictors had turned out in force, consisting of 50 policeman, 40 soldiers, 4 bailiffs, 1 solicitor and one elderly landlord’s agent (witheringly described as that “miserable creature, whose name is Perrot” by Fr Ferris).

Part II: The Eviction

An evicting party near 100-strong to eject one middle-aged priest seems a bit excessive until you consider that—the tolling of the chapel bell drawing an ever bigger crowd—there were several thousand people squeezed into the Parochial House yard for a finish and spilling down the hill towards Stables Cross. Indeed, though Fr Ferris was keen to stress that “no rioting took place” that day, for the evictors at least, the whole thing must have seemed on constant edge of a riot. Forced to carry out their work as they were under a barrage of “prolonged hooting, shouting and uncomplimentary remarks, its warmth increasing as the vile work progressed”. Eventually the police chief could take it no longer and threatened to send five policemen to arrest the bellringer if that incessant tolling wasn’t silenced immediately.

Curate Fr Hennessy reluctantly complied, but this was unlikely to have lowered the din much, what with two brass bands (from Rathcormac and Conna) playing “inspiratory strains of Irish music” the whole time the eviction was taking place. Indeed, the evictors must have despaired at the whole thing turning into a circus but they pressed on with their grim business nonetheless, carting out the priest’s belongings to pile them in the driveway. Such ignominious treatment would have reminded onlookers of the persecution of priests in Penal Times and the parallel was not lost on Fr Ferris. Indeed, meeting “the enemy outside” to give him a “bit of our mind,” he framed his dispossession squarely in those terms:

Felonious Landlordism will not always have its own way in this country and then the land thieves may look out for themselves. The man that is perpetrating the legal robbery of today is already in possession of stolen property. In fact all the property that he holds here was confiscated from our Catholic Forefathers. The original title deed was based on an act of robbery, some of it sacrilegious robbery.

The man guilty of “legal robbery” and in possession of “stolen property” was of course Fr Ferris’s landlord John Walter Perrot. Though he would have hotly disputed that his holdings were ill-gotten, there was no denying that they were extensive: with residences in Monkstown and the Manor, Castlelyons, John Walter Perrot was also owner of the Barrymore estate, having picked it up for a song after the last Earl of Barrymore had been forced to sell it to pay off his gambling debts.

But one small piece in John Walter’s property portfolio, “Prospect Cottage” may have gotten its name from its rolling view down towards the village. But today Fr Ferris drew his onlookers’ attention to a prospect of a very different kind, pointing at a familiar ruin on the horizon:

Look at those abbey lands up there. To whom did they at one time belong? To the Catholic Church. They belonged to the priests and poor monks of former times. The Saxon robber came, Cromwell with his infernal troopers came, turned out the poor monks, evicted them, as I am being evicted today. Not a farthing compensation was given them. They were made beggars, their abbey was demolished. The ruins stand there still, a living memorial of their sacrilegious robbery.

And well might Castlelyons abbey seem a potent symbol of unjust evictions past when it had only come into the possession of the Barrymores in the first place after Richard Boyle, Earl of Cork, had bequeathed it to his daughter Lady Alice Barrymore “to buy her gloves and pins”. A rather frivolous use for which to put a property from which monks had been evicted, one would think.

In any case, John Walter was wise enough to stay well away that day but, had he gotten wind of what Fr Ferris said that day, it would have galled him to hear himself compared to the most hated man in Irish history:

The man who has sent the sheriff here today … now it is not enough for him to hold the lands from which these poor monks of former times were evicted he must do a little spoliation himself by law, he must act the Cromwell himself. He must turn out a priest of the present day, rob him, cast him on the roadside as the poor monks of former times were cast, and leave him not a place where on to rest his head.

Yet, stirring though these words may have been, they could not hold back the inevitable and so by two o’clock, “the doors [were] locked and secured” and the eviction was done. Still, in this one regard at least the locals were determined not to let the evictors have it all their own way. Perhaps they had taken to heart Fr Ferris’s casting of Castlelyons Abbey as the symbol of unjust evictions past for Mary Smith remembered that “the windows and doors were removed from his [Fr. Ferris’s] house so that no-one would take the house while the priest was without a home”. As if it too should stand as “a living memorial of their sacrilegious robbery.”

These small acts of defiance aside, however, that didn’t change the harsh reality: Fr Ferris was now homeless and thus left with no choice but to fall on the generosity of his parishioners who had prepared a hut for him on some waste ground near the church in anticipation of this day. Still, down but not out, he paraded off to his new home: local man Willie Mackey remembering him leaving the house with a very large crowd. And receiving a guard of honour to boot for the road down to the village—“the priest’s hill”—lived up to its name that day, lined as it was with priests from the diocese.

Reaching the hut, Fr Ferris thanked everyone for attending the eviction. Perhaps, the crowd ebbing away, there was a sense of anti-climax: the sudden quiet seeming a little oppressive after the excitement of the day. Certainly there was a strange new reality to get used to: ministering to his flock from now on while living in emergency accommodation.

Part III: Interconnections

Let us leave him in his hut a while and take a step back to consider the big picture. In terms of tracing the interconnections of the “historic trio” buried in Castlelyons church and grounds, Thomas Kent and an tAthair Peadar’s connection may seem the more striking for their crossing paths on the most fateful day of the rebel poet’s life (see Thomas Kent page). Yet Thomas’s relationship with Fr Ferris may have been the more meaningful for going back a long way. For instance, Thomas was there for the start of Fr Ferris’s Land League journey: no doubt joining in the “great applause” that day in 1880 when, a mere boy of fifteen, he was part of the crowd that witnessed Fr Ferris’s election as the chairman of the Castlelyons branch of the Land League. And he was there for the end as Fr Ferris had only months to live when he visited Thomas in Cork gaol in 1890, where he was serving two months for conspiracy to evade the payment of rents.

But perhaps their most poignant intersection was posthumous and came in the form of a relic of Fr Ferris that somehow managed to make it through the Siege of Bawnard unscathed. As William Kent (Thomas’s brother) related in his account of the day that RIC and soldiers laid siege to their home:

Not a pane of glass was left unbroken. The interior was tattooed with marks of rifle bullets. The altar and statues in the Oratory alone escaped destruction. All around the altar plaster was knocked off the walls but not one of the statues was struck. At one time the fire of the attackers was attracted to the window of the Oratory where they thought a girl was firing at them. Strange to say, it was the statue of our Lady of Lourdes they saw from outside. The same statue was bought by my brother Tom at the sale of Father Ferris’s household effects. Father Ferris had brought it from Lourdes and I attribute to it the fact that our lives and home were saved from complete destruction.

No doubt the Kents were grateful for the momentary respite when the besiegers mistook a statue of Our Lady meek and mild for a girl firing at them. But William was convinced that something more was at play. After all, this statue could very well have been among Fr Ferris’s belongings the day he got evicted and now here it was at Bawnard, playing some small part in protecting the Kents the day that they were being violently ejected from their own home. And well might the evicted priest feel a fierce solidarity with the Kents as their house was being blown to bits around them when, in the words of the ballad, he too knew what it was to be “forced out … with bayonets fixed” and your “mansion left in ruins”.

Maybe there was a brief apparition of Our Lady of Lourdes in Castlelyons on 2nd May 1916 and maybe there wasn’t, but it seems telling of how the Kents saw themselves that William, in his 1947 statement to the Bureau of Military History, should introduce himself as “the last survivor of the band of local Land League fighters against tyrannical landlordism”. Only natural then for the Brothers Kent to view the Youghal priest as a comrade in arms as, when the Land War flared up again in Barrymore territory in 1889, it was a case of “Once more unto the breach” for Fr Ferris.

Incredibly, he was still living in the same hut, the one only ever built as a stopgap and which no-one envisaged him living in long-term. Yet here he was almost seven years later in a “timber hut” which parishioner Mary Smith remembered as “very damp” and “leak[ing] rain for a finish”. Still, despite the years of living rough taking their toll, when another of his parishioners was evicted, he was not slow to take up his cause. Said parishioner was Richard Rice (Mrs Kent’s nephew) who had been evicted from his farm. Negotiations were underway to restore Richard to his farm when suddenly it was sold out from under him to an Northern Irish man called Orr McCausland. An absentee landowner, McCausland hired a Scotsman, Robert Brown, to work the farm in his stead.

PART IV: The Coolagown Conspiracy

But the posting up of a placard in late July marked an escalation. Fr Ferris was among the chief signatories of an announcement which read:

A special meeting of this branch will be held on Sunday 28th July at Coolagown. The people are requested to attend and to show by their presence that they do not approve of land-grabbing, and that the land-grabbers will have to glut their greed elsewhere than in Coole.

Signed: Rev. Thomas Ferris, PP. Castlelyons, president; D. Hegarty, Edmond Kent, Hon. Sec.

Needless to say, at a time when “landgrabber” was the worst insult you could hurl at anyone, the entire parish was up in arms and people weren’t long making their displeasure known. For instance, drawn back from Boston by his cousin’s eviction, Thomas Kent was one of the boycotters who tried to prevent the sale of McCausland’s pigs at a fair in Fermoy in June 1889.

Near 300 people attended the protest meeting and, addressing the crowd, Fr Ferris showed that he had lost none of his fire, referring, in the course of his speech, to the Ponsonby evictions (a recent case in Youghal when a rent strike by tenants had almost driven their landlord to the edge of bankruptcy) and promising that they would get “a taste” of the same in Coolagown. He also denounced men of Brown’s ilk, claiming that a man who took a farm from which another had been evicted because he could not pay impossible rent was “a land-grabber” of the worst type.

But it was his curate Fr Jeremiah O’Dwyer who really got the crowd worked up with the following speech:

We are here today to band ourselves together … It is Mr Rice’s case today, it may be yours tomorrow. Will you suffer the evicted tenant to be cast on the roadside? (Cries of: “No!”)

He went on to leave his audience in no doubt as to who was to blame:

Old Brown was a black sheep, and they hunted him out of Scotland, and how will he rest here? I leave it to you will he be allowed to work the farm here?

Well, it is for you to say the word, and when you say the word stick to it. Do not allow anyone to grab a farm, and do not allow anyone to work a grabbed farm; if you do it will be a disgrace to your posterity. Let the word go to Brown and let him send it up to his master in the North.

In the days and weeks following, the acts of harassment mounted. Most were just petty: for example, Thomas Kent was accused of throwing eggs at Brown’s car while his brother David was meant to have blown horns at him and called him a “land-grabber”. But others were more sinister like when Brown was assaulted at Coolagown Cross while returning home from a religious service. He eventually became such a pariah locally that the military barracks in Fermoy had to supply him with food as no shopkeeper would have any dealings with him.

To be fair, all these tactics were right out of the playbook espoused by the president of the Land League himself at the start of the Land War:

When a man takes a farm from which another man has been evicted you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him; you must shun him in the streets of the town; you must shun him in the shop … and even in the place of worship by leaving him alone, by putting him into a moral Coventry, by isolating him … as if he were the leper of old – you must show him your detestation of the crime he has committed.

—Charles Stewart Parnell, Ennis meeting, 19 September 1880.

Parnell framed shunning as the “more Christian and charitable” way to pressure landlords and their agents into changing their ways. The trouble with urging people to treat others like “the leper of old” was that they sometimes took it too far. Addressing the crowd in the Chapel Yard, Fr O’Dwyer showed himself similarly careless of this contradiction, reaching on the one hand for the ideal of passive resistance when he impressed upon his listeners: “No man will, I am sure, work on this farm, no carpenter, blacksmith, or anyone else; but when he is asked he will put his hands in his pockets and say ‘good morning’”. In other words, this was to be a campaign of civil disobedience, emphasis on the word civil in that nobody was to lay hands on anyone.

Yet such highminded ideals did not stop him, in the very next breath, from casually trotting out the prospect of violence for the benefit of the police listening: “Now, constables, be on the look-out. Watch these cattle. Watch the hay and the house. The house will be set fire to”. What matter if he quickly followed this up with “but I promise you that no man, woman or child here will have anything to do with it” when such niceties were likely lost on the more hot-headed in the crowd? And, indeed, in the weeks following police had to be posted at Brown’s farm 24/7 for fear of someone making good on Fr O’Dwyer’s prediction of his being burnt out of house and home.

Yet, when the alternative was to sit back and watch people slowly get crushed by an oppressive system, it’s hard to see what other options men like Fr O’Dwyer had. After all, taking Fr Ferris’s case as an example, when the man bleeding you dry can mobilise 50 police and 40 soldiers to enforce his will, the only safety you had was in numbers. That safety lasted only as long as everyone kept their nerve. As soon as someone wavered the whole thing buckled, leaving you exposed. Which meant the constant need to stir animosity to get people to hold the line.

In any case, the campaign against Brown gathered pace over the next month until the authorities issued summonses to ten men—identified as the ringleaders of the boycott—to appear before Fermoy court on 9th September 1889, where they were to answer to charges of conspiracy to intimidate a landlord’s agent (hence the whole affair becoming known as “The Coolagown Conspiracy”). Fr O’Dwyer was charged along with them for “inciting others to use intimidation against” Brown.

The week-long trial ended in Fr O’Dwyer, David and William Kent all receiving prison sentences (Thomas, so recently returned from Boston, escaped a court summons this time). Fr O’Dwyer was released from jail in late March 1890. He made a triumphant return to Fermoy on the 3rd of April, arriving by the 4:30 p.m. train. A huge crowd turned out to greet him, crowding around his carriage to shake his hand. Thinking back to when he had been the people’s champion in 1883, Fr Ferris might be forgiven for thinking that his curate had eclipsed him. But far from feeling upstaged, he was evidently excited by his curate’s return, being one of the earliest arrivals at the station despite the very bad weather.

PART V: EIGHT YEARS A PRISONER

Serving six months in Tullamore, one of Ireland’s toughest prisons, Fr O’Dwyer well deserved his hero’s welcome. But what was perhaps lost sight of in the excitement over his release was that Fr Ferris was already almost eight years into his own prison sentence. Granted, the door to his prison cell—or, should I say, his hut in Castlelyons churchyard—was always open and, point long since made, nobody would have thought the less of him for quietly moving out into more comfortable accommodations. But he never did, not even when it was clear that living rough was ruining his health.

Perhaps he felt that he couldn’t move out; that as long as people were being evicted in his parish, he must continue to be like that building, Castlelyons Abbey, pointed to on the day of his own eviction: worn down and exposed yet somehow still standing. The way he saw it, it was imperative to find the strength of will to keep at his vigil, continuing to dwell, in the words of the ballad, “in a lonely hut / Surrounded by the tombs”. Until the fight for the Three F’s was won.

Until then he would serve, in his dereliction, as a living reminder of the greed of landlords present just as Castlelyons abbey still stands as a “living memorial” of the injustice of evictions past.

Alas, it all got too much for him in the end and—an ominous sign—at a Land League meeting in Castlelyons in October 1890 he was reported as “unable to attend due to illness”. Apparently with little hope of his recovery anytime soon as they elected someone else in his place as president.

Then, in February 1891, news reached an tAthair Peadar Ó Laoghaire in Doneraile that “the parish priest of Castlelyons was dying”. Not long afterward, on 10th February 1891, he received a letter from the bishop informing him that Fr Ferris had died and that he was to go to Castlelyons to replace him as parish priest.

Fr Ferris passed away in his hut on 7th February 1891 and Mary Smith was not alone in supposing that living rough had “shortened the priest’s life for he was only 60 when he died.” As it happened, the year that Fr Ferris died was the end of an era in more ways than one for Charles Stewart Parnell also died in 1891. Alas he had torpedoed his political fortunes the previous year by becoming embroiled in a divorce scandal which split his movement down the middle. The fight for tenant farmer rights limped on but never with quite the same force as back in Fr Ferris’s heyday.

As tends to be the case with wars of attrition, the fight for tenant farmer rights took a long time to win. But thanks to staunch campaigners like Fr Ferris, that staggeringly unjust ratio noted on the eve of the Land War—3% of Irish farmers owning their own land—had reversed itself by 1929: now 97% of Irish farmers owned their own land.

A line from Fr Ferris’s marble epitaph high up on the wall in Castlelyons church springs to mind in this context: AN UNFLINCHING PROTECTOR OF THE POOR AND THE OPPRESSED. Because that’s the thing, you see, he didn’t flinch. Not when it came to putting his own health on the line for his parishioners’ sake. Perhaps it was a case of his heeding the motto carved above the skull and crossbones on the holy font to the right of the main door which he would often see on his way into church: Cum sit vita brevis discito bene mori, “Since life is short, learn to die well.” If dying well means sticking to your principles to the very end, then he did indeed die well.

If curious about where his hut was, then you should head out to the fishpond where you’ll find a plaque marking the spot. Then maybe spare a thought for the man who “suffered not a little” standing up for poor farming folk.

SOURCES

Britway – Castlelyons – Kilmagner: Reunion 1991. Cork: Castlelyons Committee, 1991.

O’Brien, Eilish and Pat. Mise an Mac San: Remembering an tAthair Peadar Ó Laoghaire. Cork: Sciob Sceab, 2018.

Ronayne, James. “Tribute to evicted priest who spent 11 years in hut.” 07 Jul 2017 <https://www.echolive.ie/corklives/arid-40181061.html>.

Ryan, Meda. Thomas Kent: 16 Lives. Dublin: O’Brien P, 2016.