Part I: The Seven Grammatical Errors

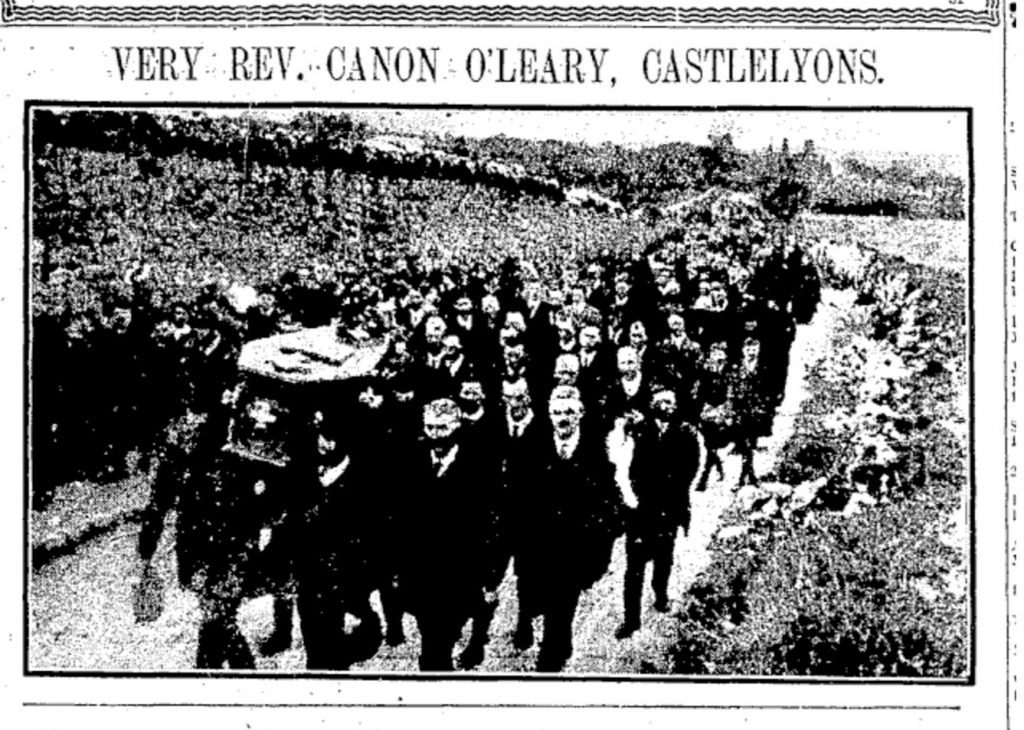

Picture the scene: Tuesday, 23rd March 1920, just after 11 o’clock mass. A sombre crowd in Castlelyons churchyard. A bearded gentleman watches a coffin being lowered into the earth. Suddenly he grumbles: “Disgraceful! That coffin plate has at least seven grammatical errors!”

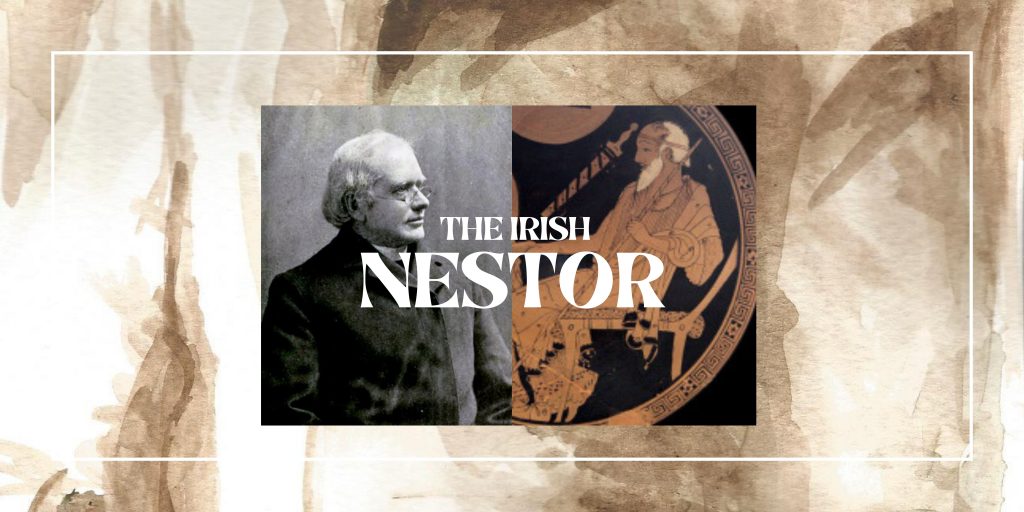

Who’s that, you ask? That’s Osborn Bergin, “prince of Gaelic scholars”. Such nitpicking would have seemed tactless coming from anyone else, but not so much Osborn when everyone knew what a stickler he was about grammar. Besides, it may have been pity that moved him to fault the coffin plate, knowing that it would bother his old friend to spend eternity with ungrammatical Irish on his coffin. How could it not when they were gathered here today to say goodbye to none other than an tAthair Peadar Ó Laoghaire? A man equally particular about grammar if the following statement is any indication:

Before I left Liscarrigane, I never heard phrases like “Tá mé”, “Bhí mé”, and “Bhí siad”. I used always hear “Táim”, “Bhíos”, and “Bhíodar”, etc. Little things, but little things that come repeatedly into conversation.

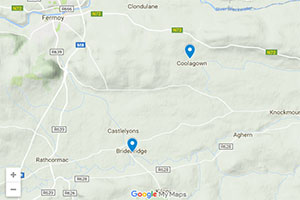

Where’s Liscarrigane? It’s townland in Clondrohid near Macroom where an tAthair Peadar was born in 1839. It was also home to his sister Máire Ní Laoghaire before she moved to Castlelyons to live with her brother. As it happened, there was a Castlelyons woman among the mourners at an tAthair Peadar’s funeral with a story to tell about Máire that showed how it was a very different place from where Máire and Peadar grew up in the Muskerry Gaeltacht. She was Mrs Mary Smith and her grandparents were native speakers of Irish (13% of the Fermoy area were still native speakers in 1891.)

So the story goes, Máire was walking down from the priest’s house one day when she met an old woman walking up the hill against her. She greeted her in Irish only to get the affronted response: “Why I can speak English as good as yourself!” Mrs Smith chuckled to recall this but it serves as a reminder of the shame felt at speaking Irish publicly in early twentieth-century Ireland for fear it be taken as a sign that you were poor and ignorant.

An tAthair Peadar did much to lessen this stigma, not least by championing Gaeltacht Irish as the basis for modern Irish at a time when others wanted a return to the seventeenth-century Irish of Geoffrey Keating. In filling his first novel with Gaeltacht Irish, he also showed native speakers that their everyday language could rise to the level of art, as Patrick Pearse acknowledged when he said of Séadna: “Here at last we have literature!”

On that March morn in 1920, Máire must have thought her brother’s fame assured. After all, people were unlikely to soon forget the man once put on a par with the great English novelists:

What Thackeray and Dickens have done for English literature Father O’Leary has done for Irish.

—W.T. Cosgrave, 1911

Nor did a slow slide into oblivion seem likely for a man once deemed such a household name that it was said of him:

almost every man, woman and child in Ireland, who has ever handled an Irish book knows the name and loves it.

—Seán T. Ó Ceallaigh, 1911.

But perhaps the greatest insurance against being forgotten were all the literary firsts that he had achieved:

- First play in modern Irish: Tadhg Saor in 1900.

- First novel in modern Irish: Séadna in 1904.

- First autobiography in modern Irish: Mo Scéal Féin in 1915.

Alas, the seven grammatical errors on his coffin would prove an omen of things to come as an tAthair Peadar’s fame did go into decline after his death to the point that few remember him today.

It started with people tiring of putting him up on a pedestal. Witness Brian Ó Nulláin’s 1941 novel An Béal Bocht. Set in a Gaeltacht where the locals recognise the coming of spring not by the first swallow but by the first “Dublin Gaeilgeoir” spotted on the roads, knowing Séadna is depicted as a badge of identity for any self-respecting Irish speaker: “Have you ever read Séadna? the Auld-Fella asked sincerely”. Yet Ó Nulláin poked fun at painfully-earnest Gaeilgeoirs for invoking an tAthair Peadar as their be-all and end-all: “Nee doy lum goh vwill un fukal sin ‘meath’ eg un Ahur Padur,” arsa an Gaeilgeoir go cneasta.” Their clumsy Irish was sign enough that their judgment was not to be trusted.

There were even some rumblings of discontent back when it was still taboo to point out that the Gaelic Revival’s golden boy had feet of clay. Witness V. L. O’Connor’s c. 1916 drawing (now in the National Library of Ireland) of an tAthair Peadar attacking a startled young man with a blunt meat cleaver. This was likely a cheeky swipe at his habit of attacking people in the newspapers, usually with a strongly-worded letter to the editor. But the cartoonist baulked at publishing his send-up of a national treasure, pencilling a note on it: “Dangerous: not for publication”.

The disenchantment strengthened in the 1970s when attention was drawn to the priest’s obstreperousness in his dealings with his long-suffering editor Eoin Mac Neill. Their friendship came under strain when Mac Neill cancelled Séadna’s run in The Gaelic Journal. The row escalated with the Castlelyons cleric insisting that “I must be allowed to write blíaghaín or blíadhaín just as I like!” Yet his demand was not entirely unreasonable once you consider his golden rule for producing authentic Irish:

Any man who wants to write lrish has nothing to guide him but the pronunciation of those who speak the living language still … he must use his ear the first of all.

Part II: The Tuning Fork

In demanding that he be allowed spell just as he liked, an tAthair Peadar was therefore arguing for phonetic spelling. A vital tool, as he saw it, for capturing on paper the linguistic knowledge of native speakers before they went the way of the dodo. It wasn’t that he didn’t see the necessity of standardized spelling, just that he thought that it was being imposed prematurely before language conservationists like himself had a chance to gather the best specimens from the wild.

And, in his own eyes, there was no man better equipped for this delicate work than himself, as evident from this 1899 letter of his: “It is a sad fact, but it is a real fact, that no other living human being knows how to handle the language as I do.”An egotistical statement on the face of it but not without some foundation if you consider the early makeup of the Gaelic League, according to Pádraig Ó Fiannachta:

The majority of those in the Gaelic League in its early days were learners of lrish. The early writers of the Gaelic Revival were the same. Only a very few native speakers were able to read or write. lt was the learners then who were in charge when it came to writing.

Mac Neill was quick to see how unique an tAthair Peadar was in this regard. Witness his excitement in introducing the first chapter of Séadna to Gaelic Journal readers in 1894: “One of the best samples, if not the very best, of Southern popular Gaelic that has ever been printed”.

Listening to Irish from the cradle, an tAthair Peadar knew that it had a music to it when voiced by a native speaker. He even used the analogy of a tuning fork when advising learners to listen to Gaeltacht speakers to attune their ear to the rhythms of the language. Hence why the plodding sound of book-learnt Irish grated on him so; or, as he put it: “it is like your Irish is looking at its feet.” As for “Mr. Mac Neill”, he sniffed, the trouble with him was that he “had no tuning-fork”. How then could his likes be trusted to fix the spelling of Irish when they were deaf to the music of the same?

Part III: Devil on Two Wheels

In defending Irish from those would mangle it, an tAthair Peadar did not shy from pointing out the deficiencies of others. And so too, with time, critics were not slow to point out his limitations as a writer. This led to the slow erosion of his literary standing to the point where few scholars would regard him as a great author today. Yet, before dismissing him as a hack, we would do well to remember the pressure under which he wrote. For, when he first picked up his pen at the relatively late age of fifty-five, there was little or no reading materials in Irish. With native speakers dying off in their droves, he therefore felt in a race against time to get down on paper the beautiful strain of Irish heard by Muskerry firesides in his youth. This sense of urgency meant that he didn’t always put the same effort into his plots, which in turn meant that his novels haven’t stood the test of time in the same way as, say, the novels of Dickens or Thackeray have.

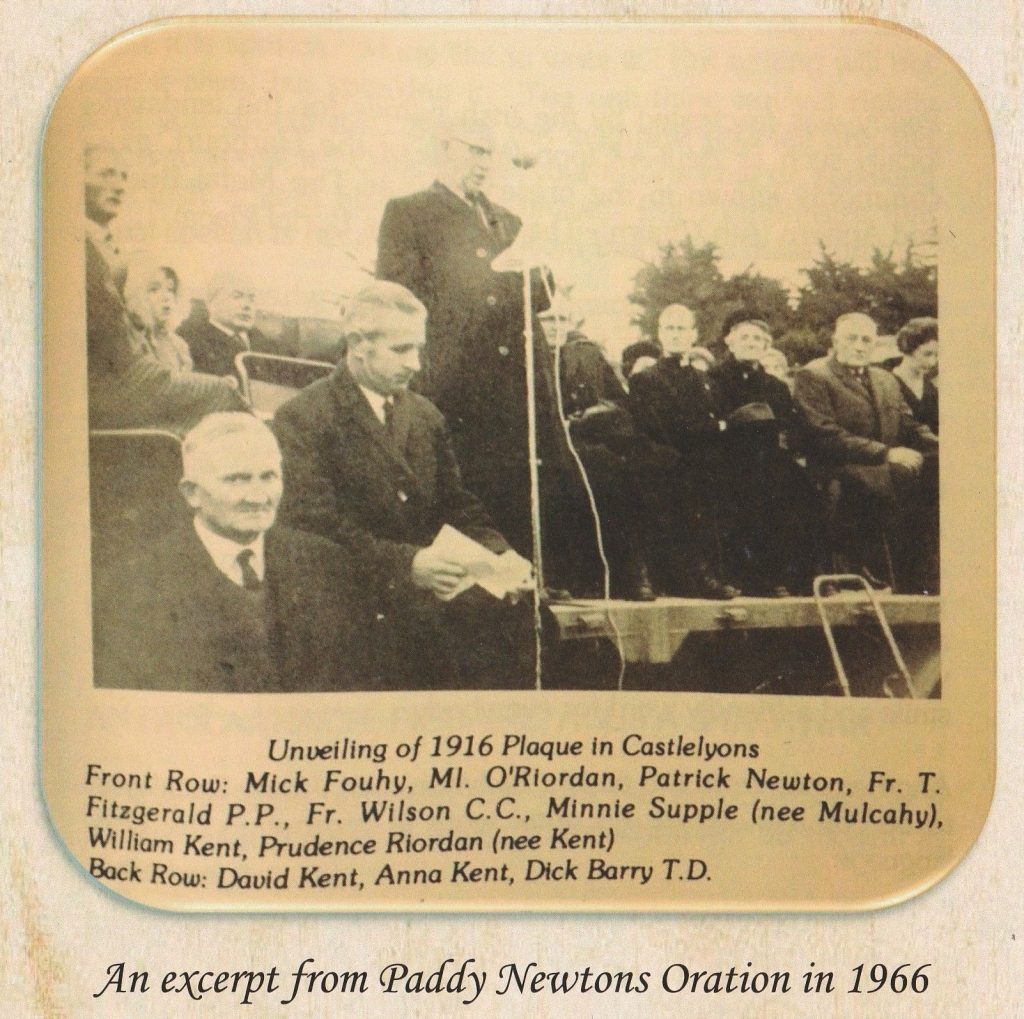

Add to this a certain intrepidness, bordering on rashness, when it came to trying new things, even when getting on in years. A trait perfectly captured by an anecdote told by local man Paddy Newton. Paddy was born in “Knocknagopal near the Bride”, a townland in Aghern. Most people still spoke Irish in Knocknagopal when Paddy was born there in 1884 with the result that, in his words, “the sound of Irish was the first sound to fall on my ears”.

And, listening to him in a radio interview from the RTE archives, Paddy (or Pádraig Ó Nuatáin as he was also known) certainly had the blas (that is, that natural way of speaking Irish that comes from speaking it from an early age). Though born just across the border in Aghern, he seems to have had a strong connection with Castlelyons, a connection perhaps partly explained by some Newton graves in Castlelyons graveyard. Most recent of these is a headstone “Erected by Ansty Newton of Knocknagapol in loving memory of her husband John Newton” who died in 1848.

A Castlelyons connection may also explain why, as Paddy recalled in his interview, his family used to go to first mass in Castlelyons every Sunday. Paddy was tasked with driving the horse and cart to get his family to church and it was in this role that he first met an tAthair Peadar, giving him a lift home from Mass one Sunday. Not much was said that first morning but, over the course of many lifts home, they became great friends, Paddy remembering how “every Sunday he used always have a funny story for me.”

To turn to the anecdote that showed an tAthair Peadar’s intrepid streak, the incident happened when Paddy was around nine (putting the year at 1893). He was in a field helping bring in the corn when:

a boy ran into the field to us, scared out of his mind. He ran over to one of the harvest men whom he knew and said “Oh, oh, oh! He’s after me! He’s after me!”

“Who’s after you?” the harvest man asked.

“He’s coming over the road,” the little boy said “and he’s up on two wheels.”

“Who is?” the harvest man asked.

“The devil,” he said. “The devil! He’ll be here any second now,” he said, “and God only knows what he’ll do if he catches up with me!”

The harvest man knew that the boy had seen something unusual and so he went out onto the road with all of us following. But no sooner were we out there than we saw the man on two wheels coming towards us but, instead of the devil, who should it be but an tAthair Peadar and one of those bikes as his means of transportation that they call the penny farthing.

(Incidentally, you can listen to the full interview here: https://www.rte.ie/radio/rnag/clips/21520405/).

The little boy had obviously never seen a penny farthing before and the strangeness of the contraption was only increased by seeing a man balanced precariously atop it, dressed all in black. Seeing it barreling down the road towards him was all too much for him and he took fright, convinced the devil himself was after him.

But the nightmare on wheels was only an tAthair Peadar out for a spin in his priestly garb. Which just goes to show that, while dreadfully old-fashioned in some ways, he was ahead of his time in others. And it was this intrepid mindset (as illustrated, for example, in being an early adopter of the bicycle) that saw him reach new heights as a writer but also marked him out as a bit of an odd duck in a quiet country parish like Castlelyons.

In terms of the progression of his literary career, one can almost imagine his thoughts as follows: No-one’s ever written a play in Irish, you say? Might as well have a go. Or What do you mean no-one’s written a novel in Irish yet?! How’s anyone supposed to learn Irish?! Better do something about that. The trouble with being the first to write in so many genres, however, was that he wrote without any precedent to guide him. Subsequent writers therefore had the luxury of learning from his mistakes, something Patrick Pearse seemed to understand when he wrote:

The formative influence of ‘Séadna’ is likely to be great. Some of our most distinctive writers have declared that it was the early chapters of ‘Séadna’ which first taught them to write lrish. Not that they admit themselves mere imitators of Father O’Leary, but rather that ‘Séadna’ showed them how to be themselves.

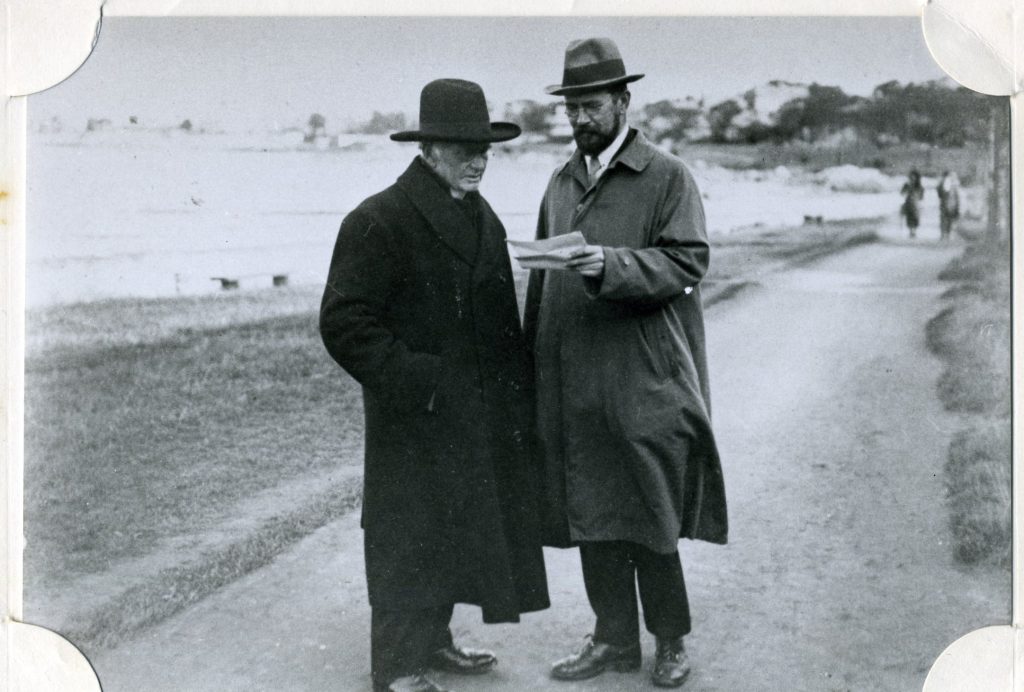

(Courtesy of Prof. John Breslin, NUIG)

So we would do well to bear in mind that later writers might not have been able to write as fluently as they did if they did not have his writings for a model. A debt poet Seán Ó Riordán acknowledged when he wrote in his diary, New Year’s Day, 1940: “I like an tAthair Peadar’s style more than any other writer that I have encountered in Irish so far … The echo of this man will set my pen dancing from page to page.”

Writing in 1989, Cyril Ó Céirín summed up an tAthair Peadar’s legacy as follows: “Because of the lead he gave and the paths he explored, it could be said that he created a literature single-handed’. To hear him described in this way, you would think him an intrepid explorer. And there was something dauntless in the way he tried genre after genre, regularly setting off into uncharted territory with only a vague idea of what he was letting himself in for.

Did his willingness to try new things sometimes lead to his biting off more than he could chew? Absolutely. Would literature in modern Irish be the poorer without his audacious example as a precedent? I think so, yes. Interestingly, in likening an tAthair Peadar to Dickens in 1911, W. T. Cosgrave preceded his comparison with the line: “His works are a quarry from which all … can hew stones to rebuild our national literature—they are a mine of Celtic wealth.” Perhaps this then is the best way to give the “devil” (on his bicycle!) his due: in the early days of the Gaelic Revival, an tAthair Peadar worked ceaselessly to provide the reading materials in rich Gaeltacht Irish that were in such short supply. Immersing themselves in his writings, later, better writers soon outstripped him but it would have been harder to achieve fluency without his writings as raw material. In this way then his pioneering writings had a lasting impact that can be felt right down to our own day.

Take his inspiring example out of the Gaelic Revival and, who knows, the movement could have gotten off to a far shakier start. Certainly, without him to speak up for native Irish speakers, the Revivalists could have headed down another road, one that ended in the folly of trying to resurrect a version of the language three centuries dead. One thing’s for sure: a wealth of linguistic knowledge was lost the day that they buried an tAthair Peadar.

God rest those seven grammatical errors.

SOURCES

Britway – Castlelyons – Kilmagner: Reunion 1991. Cork: Castlelyons Committee, 1991.

Breathnach, Diarmaid, and Máire Ní Mhurchú. “Ó Laoghaire, Peadar (1839-1920)”. Ainm.ie

26 March 2022 <http://www.ainm.ie/Bio.aspx?ID=210>.

—. “Osborn, Bergin Joseph (1873-1950)”. Ainm.ie 26 March 2022

< https://www.ainm.ie/Bio.aspx?ID=122>.

Ní Mhaonaigh, Tracey, Ed. Tháinig do Litir: Litreacha ó Pheann an Athar Peadar Ó Laoghaire chuig Séamus Ó Dubhghaill. An Daingean: Sagart, 2017.

“Nollaig Ó Gadhra i mbun agallaimh le Pádraig Ó Nuatáin.” Siúlach Scéalach 030319. RTE Raidió na Gaeltachta. 03 March 2019

<https://www.rte.ie/radio/rnag/clips/21520405/>.

O’Brien, Eilish and Pat. Mise an Mac San: Remembering an tAthair Peadar Ó Laoghaire. Cork: Sciob Sceab, 2018.

Ó Dúshláine, Tadhg, ed. Anamlón bliana: ó dhialanna an Ríordánaigh. Conamara : Cló Iar-Chonnacht, 2014.

Ó Nualláin, Brian (aka Myles na gCopaleen). An Béal Bocht. Cork: Mercier P, 1999.